After ample consideration, we decided that the best way ahead was to use pipeline templates as preferred deliverable to our users.

Pipeline templating is a powerful feature within Azure DevOps

You can abstract pieces of your pipelines into separate template files, which can then be re-used across other pipelines. This functionality especially shines within large, corporate environments. In these large corporations, tooling for software development is usually standardized and often restricted in many ways. With so many software developers using the same toolkit, it makes sense to provide standardized toolchains to ensure best engineering practices between development teams.

When my team and I were working on the front-end templates, we found that the functionality of templates is actually so flexible that there are many ways to expose these to the template-consumers.

Now, the different ways of interfacing range widely in complexity, flexibility and composability. Each situation requires its own type of template and choosing the wrong template interface can make the solution more complex than intended. This sparks some questions: how to structure these templates? What’s the best way to make sure they are simple enough to interface with, yet provide enough functionality?

In this blog post I will go over a few ways to organize your templates, along with some use-cases and pro’s and cons.

Note: In the examples, I use some front-end terminology. However, the concepts of templates are the same for any type of project.

The ‘One template to rule them all’

Template

# File: template.yaml

# Whole flow from start to end

stages:

- stage: Install

steps:

- bash: echo "registry=https://my.npm.domain/api" > .npmrc

- task: Npm@0

displayName: Npm install

- stage: Build

steps:

- task: Webpack@0

displayName: Webpack build

- stage: Test

steps:

- task: Mocha@0

displayName: Mocha test

- stage: Publish

steps:

- bash: echo "registry=https://my.npm.domain/api" > .npmrc

- task: Npm@0

command: publish

displayName: Publish NPM packageConsuming pipeline

# File: azure-pipelines.yaml - template: template.yaml

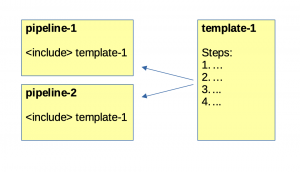

This type of template works very well when multiple pipelines need to run the exact same steps. For example, we have about 12 Azure DevOps extensions living in separate repositories. Each of these extensions need to be built, published and installed in the exact same way.

For this use-case, we have one `template.yaml` in a central repository. Each of the `pipeline.yaml` include this template in the exact same way, effectively saving 12 copy-pastes, whenever we need to change the pipeline.

All set?

Not quite yet, this type of template is not very suitable for customizations. To allow any customization of this template, you will need to add template parameters which resolve into conditionality. For complex pipelines, this approach gets out of hand quickly, and you might end up with many parameters and if-conditions, which is not desirable.

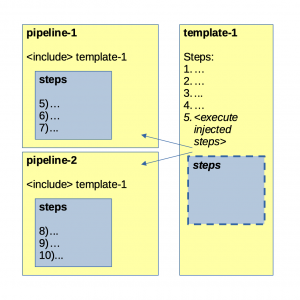

Customization through step injection

Template

# File: template.yaml

# Let template consumer define buildsteps

parameters:

- name: buildsteps

type: steplist

stages:

- stage: Install

steps:

- bash: echo "registry=https://my.npm.domain/api" > .npmrc

- task: Npm@0

displayName: Npm install

- stage: Build

steps:

# Execute buildsteps

- ${{ each step in parameters.buildsteps }}:

- ${{ step }}

- stage: Test

steps:

- task: Mocha@0

displayName: Mocha tests

- stage: Publish

steps:

- bash: echo "registry=https://my.npm.domain/api" > .npmrc

- task: Npm@0

command: publish

displayName: Publish NPM package

Consuming pipeline

# File: azure-pipelines.yaml

- template: template.yaml

parameters:

# Injecting the build steps

buildsteps:

- task: Rollup@0

displayName: Rollup build

- most of the pipeline is fixed

- little customization is required

- the possible steps are not known from the template perspective

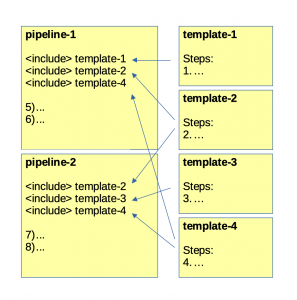

The ‘mix-and-match’ approach

Let’s break up our pipeline in small templates and assemble these together in a main pipeline.

Template

# File: templates/install.yaml

steps:

- bash: echo "registry=https://my.npm.domain/api" > .npmrc

- task: Npm@0

displayName: Npm install

```

```yaml

# File: templates/build.yaml

steps:

- task: Webpack@0

displayName: Webpack build

```

```yaml

# File: templates/test.yaml

steps:

- task: Mocha@0

displayName: Mocha tests

```

```yaml

# File: templates/publish.yaml

steps:

- bash: echo "registry=https://my.npm.domain/api" > .npmrc

- task: Npm@0

command: publish

displayName: Publish NPM packageConsuming pipeline

# File: azure-pipelines.yaml

stages:

- stage: install

steps:

- template: template-install.yaml

- stage: build

steps:

- template: template-build.yaml

- stage: test

steps:

- template: template-test.yaml

- stage: publish

steps:

- template: template-publish.yaml

Conclusion

The freedom that our users now have, stands in contrast to our previous pipeline offering, which was more fixed and restrictive. The restrictions led to frustration to some of our power-users in the past. Needless to say their experience is more positive now 😉

To recap, I think it’s important to consider who is consuming your templates and with which use-case. Do all of your consumers need the same pipeline, or do they want to customize their pipeline completely?

Either way, I am sure you too will find, there are template styles to match their needs.